How standardised classroom tests are producing some frightening outcomes in the US

by Gordon Campbell

Testing kids in the classroom sounds like a good idea. Surely that keeps tabs on how they’re doing, and identifies which kids might be falling through the cracks…and that’s all good, right? Well…except that most teachers have alwaysdone testing, have always sought to detect kids at risk, and have always managed to strike a healthy balance between teaching and testing. The issue is whether the demands to follow standardised testing procedures (and the practices and attitudes that go with them ) may now be poisoning the whole environment for learning.

Testing kids in the classroom sounds like a good idea. Surely that keeps tabs on how they’re doing, and identifies which kids might be falling through the cracks…and that’s all good, right? Well…except that most teachers have alwaysdone testing, have always sought to detect kids at risk, and have always managed to strike a healthy balance between teaching and testing. The issue is whether the demands to follow standardised testing procedures (and the practices and attitudes that go with them ) may now be poisoning the whole environment for learning.

As with many other social trends, the United States provides a cautionary vision of how good intentions can come unstuck. A few months ago, the impact of testing, testing, testing in the classroom came under the spotlight when a resignation letter by a veteran US teacher called Jerry Conti went viral. You can read the entire resignation letter here:

Its salient points are here:

With regard to my profession, I have truly attempted to live John Dewey’s famous quotation… that “Education is not preparation for life, education is life itself.” This type of total immersion is what I have always referred to as teaching “heavy,” working hard, spending time, researching, attending to details and never feeling satisfied that I knew enough on any topic. I now find that this approach to my profession is not only devalued, but denigrated and perhaps, in some quarters despised. STEM [Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics] rules the day and “data driven” education seeks only conformity, standardization, testing and a zombie-like adherence to the shallow and generic Common Core [Standards] along with a lockstep of oversimplified so-called Essential Learnings. Creativity, academic freedom, teacher autonomy, experimentation and innovation are being stifled in a misguided effort to fix what is not broken in our system of public education….

Conti continues :

Conti continues :

…..My profession is being demeaned by a pervasive atmosphere of distrust, dictating that teachers cannot be permitted to develop and administer their own quizzes and tests (now titled as generic “assessments”) or grade their own students’ examinations. The development of plans, choice of lessons and the materials to be employed are increasingly expected to be common to all teachers in a given subject. This approach not only strangles creativity, it smothers the development of critical thinking in our students and assumes a one-size-fits-all mentality more appropriate to the assembly line than to the classroom. Teacher planning time has also now been so greatly eroded by a constant need to “prove up” our worth to the tyranny of APPR [Approved Teacher Practice Rubrics]through the submission of plans, materials and “artifacts” from our teaching, that there is little time for us to carefully critique student work, engage in informal intellectual discussions with our students and colleagues, or conduct research and seek personal improvement through independent study. We have become increasingly evaluation and not knowledge driven. Process has become our most important product, to twist a phrase from corporate America, which seems doubly appropriate to this case.

In the process, Conti says, school administrations have been both uncommunicative and unresponsive to the concerns and needs of staff and students “by establishing testing and evaluation systems that are Byzantine at best and at worst, draconian…” In the light of these developments, Conti could see only one possible conclusion : “After writing all of this I realize that I am not leaving my profession, in truth, it has left me. It no longer exists…”

Lest that be taken as the jaundiced opinion of one disgruntled teacher, Salon magazine recently reported some chilling examples of where the drive for standardised testing has taken some US classrooms : to the dreaded, so-called “ prep rally.” Columnist Mary Elizabeth Williams describes what that entails:

Lest that be taken as the jaundiced opinion of one disgruntled teacher, Salon magazine recently reported some chilling examples of where the drive for standardised testing has taken some US classrooms : to the dreaded, so-called “ prep rally.” Columnist Mary Elizabeth Williams describes what that entails:

Last week, the principal of my third grader’s progressive, learn-by-doing school sent home a letter about the “overemphasis on assessments and the unintended consequences of using state tests to promote students and evaluate school,” a letter in which she promised the education our students receive there “cannot be measured by a single test score.”[Yet] the next day, the faculty shepherded the entire student body into the gym to cheer for the students to “Do your best” and sing, to the tune of “Ghostbusters,” that they were “test crushers.”

The rally may have been a well-intentioned attempt to defuse students’ pre-test jitters. A school administrator later told me, “It wasn’t to further promote testing. It was just about increasing confidence.” Our principal echoed the sentiment, saying, “We did a very intense test prep this year. We recognize that our kids were saturated and starting to feel overload…. And, she noted, “The idea of bringing a group together to garner enthusiasm is something we do all the time.”

The logic of the test pep rally is described by its enthusiasts in this article from Education World which carries the headline “Big Test Pep Rallies: 2, 4, 6, 8 — Taking Tests And Feeling Great!” Maybe for some. Many others will relate far more readily to Williams’ reaction in Salon:

But the ultimate effect had a strangely “Hunger Games” tang to it – a mood of forced, rah-rah re-assurance to the terrified children going into the arena, cheered on by those too young to yet participate. Unnervingly, it was a scene being played out in other schools all around the country, as they too have prepared their students for a series of tests many have been practicing for since September. The night of the rally, I spoke to my schoolteacher friend Blair in Pennsylvania, who told me they’d done similar events at her school and both of her sons’ schools, complete with near-identical catchy songs and even merchandise giveaways. “They sang ‘I will do my best best best’ to the tune of ‘Dynamite.’ It would have been cute if it wasn’t evil,” she said. “They hang up banners in the schools that say ‘I will do my best on the test.’ We get robocalled from all three schools before the test days. It’s all almost exactly the same wording from each principal. It’s a disgrace.”

As an integral part of this process, up to half of that Pennsylvania teacher’s salary will be tied to how her students performed on their tests. As Williams notes, such a system places those teachers who work with the children of migrants who may have English language difficulties and/or those who teach children with special needs — “who might be great students but not great English language test takers” — at risk of punitive measures.

As an integral part of this process, up to half of that Pennsylvania teacher’s salary will be tied to how her students performed on their tests. As Williams notes, such a system places those teachers who work with the children of migrants who may have English language difficulties and/or those who teach children with special needs — “who might be great students but not great English language test takers” — at risk of punitive measures.

As the heart of the Salon article is the contention that the emphasis on testing is skewing the learning experience for chidren. According to one teacher quoted : “My honors English curriculum now contains only two books, instead of the 12 I used to teach. And very few short stories. It’s mostly nonfiction, because that’s what will be on the tests. Any books I teach outside of the curriculum will harm my students’ scores on the tests that evaluate them and my performance. Goodbye, ‘Lord of the Flies.’ Goodbye, ‘Macbeth.’ Goodbye, ‘A Separate Peace.’ Most good teachers are demoralized by the test, and horrified by what it is doing to education.”

Another teacher : “This afternoon I was told that I must remove all the student art work hanging in the room, as it ‘will be a distraction to the students taking the tests.’” In the process, such emphases are changing the way that students view the purpose of their education :

“Children are getting the message at a very young age that if you pick the right choice between several options you can be successful. That’s not the way to learn, especially creatively. That’s not experimenting or exploring or creating. We’re telling kids that that life is a series of hoops and that they need to start jumping through them very early.”

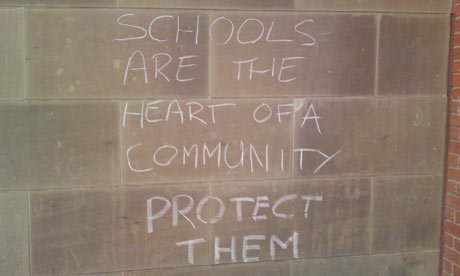

At a higher level of impact, schools that score poorly on the tests run the downstream risk of being marked out for closure, or downsizing. The Core Standards system, the Salon article suggests, is perhaps being built to fail. “All the passing ratings are going to go down about 30 percent this year; that’s what they’re predicting,” author, advocate and education historian Diane Ravitch told Salon, “The dark view is that they want everybody to fail and they want people to say the public schools stink, so they can push for more vouchers and more charter [schools]. I can’t describe what’s going on without thinking that we’re in the process of destroying American public education.”

At a higher level of impact, schools that score poorly on the tests run the downstream risk of being marked out for closure, or downsizing. The Core Standards system, the Salon article suggests, is perhaps being built to fail. “All the passing ratings are going to go down about 30 percent this year; that’s what they’re predicting,” author, advocate and education historian Diane Ravitch told Salon, “The dark view is that they want everybody to fail and they want people to say the public schools stink, so they can push for more vouchers and more charter [schools]. I can’t describe what’s going on without thinking that we’re in the process of destroying American public education.”

Most New Zealanders may be surprised to discover that the current US testing regime – and the New Zealand system of national standards that mimics it – originated with that paragon of excellence, George W.Bush. On the campaign trail in 2000 it was Bush who cited his so-called “Texas Miracle” whereby standardized testing had allegedly transformed the education system in his home state while he was governor, and this led durectly to the No Child Left Behind programme once he was elected President. It has since inspired similar ( and allegedly even more stringent) classroom testing practices under Barack Obama.

Reportedly, critics such as Ravitch do not oppose all forms of testing, only the way the process has become unduly standardised, and the status it has been given. In her opinion, such tests should be designed by the teachers, and kids should be tested based on what they’ve been taught. “Instead, the testmakers are telling educators what to teach — and that’s backwards. All of this is a terrible distortion of education.”

Absolutely, Mary Elizabeth Williams concludes, there are broken schools and faulty teachers, who are failing the needs of children every day:

But building a better system of public education – an education to which every child in this country is entitled — takes creative and innovative approaches, tailored to individual communities. Learning is not a one size fits all proposition. And our kids and our schools shouldn’t have their whole futures riding on how well children can fill in little circles, to be scored by machines. As Blair says, “We are exchanging authentic, age-appropriate learning – real thinking learning – for test taking. It makes me want to scream.”

Scream as they might, teachers and concerned parents in New Zealand are not being heard – either by the previous Education Minister Anne Tolley, or by her accident-prone successor. This is despite the evidence that far beyond the US, some countries have achieved better outcomes from their state systems by deliberately shunning standardised testing. In this informative Atlantic article, the Finnish journalist Aru Partanen cites the attributes of a Finnish school system that regularly outscores the US ( and New Zealand) in international rankings of student achievement. Among other things, Finland has no standardised testing, and no private schools at all. The key elements in its approach have been summarised as follows:

1. Finland does not give their kids standardized tests.

1. Finland does not give their kids standardized tests.

2. Individual schools have curriculum autonomy; individual teachers have classroom autonomy.

3. It is not mandatory to give students grades until they are in the 8th grade.

4. All teachers are required to have a master’s degree.

5. Finland does not have a culture of negative accountability for their teachers. According to Partanen, “bad” teachers receive more professional development; they are not threatened with being fired.

6. Finland has a culture of collaboration between schools, not competition. Most schools…perform at the same level, so there is no status in attending a particular facility.

7. Finland has no private schools.

8. Education emphasis is “equal opportunity to all.” They value equality over excellence.

9. A much higher percentage of Finland’s educational budget goes directly into the classroom than it does in the US, as administrators make approximately the same salary as teachers. This also makes Finland’s education more affordable than it is in the US.

10. Finnish culture values childhood independence; one example: children mostly get themselves to school on their own, by walking or bicycling, etc. Helicopter parenting isn’t really in their vocabulary.

11. Finnish schools don’t assign homework, because it is assumed that mastery is attained in the classroom.

12. Finnish schools have sports, but no sports teams. Competition is not valued.

13. The focus is on the individual child. If a child is falling behind, the highly trained teaching staff recognizes this need and immediately creates a plan to address the child’s individual needs. Likewise, if a child is soaring ahead and bored, the staff is trained and prepared to appropriately address this as well.

14. Compulsory school in Finland doesn’t begin until children are 7 years old.

Migration to Finland however, is not an option for New Zealand teachers. Although many of them would probably share Jerry Conti’s fears about where the undue emphasis on standardised classroom testing is leading us, and the damage it is doing to children’s creativity.

Testing kids in the classroom sounds like a good idea. Surely that keeps tabs on how they’re doing, and identifies which kids might be falling through the cracks…and that’s all good, right? Well…except that most teachers have alwaysdone testing, have always sought to detect kids at risk, and have always managed to strike a healthy balance between teaching and testing. The issue is whether the demands to follow standardised testing procedures (and the practices and attitudes that go with them ) may now be poisoning the whole environment for learning.

Testing kids in the classroom sounds like a good idea. Surely that keeps tabs on how they’re doing, and identifies which kids might be falling through the cracks…and that’s all good, right? Well…except that most teachers have alwaysdone testing, have always sought to detect kids at risk, and have always managed to strike a healthy balance between teaching and testing. The issue is whether the demands to follow standardised testing procedures (and the practices and attitudes that go with them ) may now be poisoning the whole environment for learning. Conti continues :

Conti continues : Lest that be taken as the jaundiced opinion of one disgruntled teacher, Salon magazine recently reported some chilling examples of where the drive for standardised testing has taken some US classrooms : to the dreaded, so-called “ prep rally.”

Lest that be taken as the jaundiced opinion of one disgruntled teacher, Salon magazine recently reported some chilling examples of where the drive for standardised testing has taken some US classrooms : to the dreaded, so-called “ prep rally.”  As an integral part of this process, up to half of that Pennsylvania teacher’s salary will be tied to how her students performed on their tests. As Williams notes, such a system places those teachers who work with the children of migrants who may have English language difficulties and/or those who teach children with special needs — “who might be great students but not great English language test takers” — at risk of punitive measures.

As an integral part of this process, up to half of that Pennsylvania teacher’s salary will be tied to how her students performed on their tests. As Williams notes, such a system places those teachers who work with the children of migrants who may have English language difficulties and/or those who teach children with special needs — “who might be great students but not great English language test takers” — at risk of punitive measures. At a higher level of impact, schools that score poorly on the tests run the downstream risk of being marked out for closure, or downsizing. The Core Standards system, the Salon article suggests, is perhaps being built to fail. “All the passing ratings are going to go down about 30 percent this year; that’s what they’re predicting,” author, advocate and education historian Diane Ravitch told Salon, “The dark view is that they want everybody to fail and they want people to say the public schools stink, so they can push for more vouchers and more charter [schools]. I can’t describe what’s going on without thinking that we’re in the process of destroying American public education.”

At a higher level of impact, schools that score poorly on the tests run the downstream risk of being marked out for closure, or downsizing. The Core Standards system, the Salon article suggests, is perhaps being built to fail. “All the passing ratings are going to go down about 30 percent this year; that’s what they’re predicting,” author, advocate and education historian Diane Ravitch told Salon, “The dark view is that they want everybody to fail and they want people to say the public schools stink, so they can push for more vouchers and more charter [schools]. I can’t describe what’s going on without thinking that we’re in the process of destroying American public education.” 1. Finland does not give their kids standardized tests.

1. Finland does not give their kids standardized tests.